|

||

At

last count the I-Love-You worm (virus) is responsible for billions

of dollars worth of damage. The worm was nothing special, but it was sufficiently

different to the last e-plague, Melissa, that it sailed past virus

scanners and into Windows' e-mail programs everywhere. At

last count the I-Love-You worm (virus) is responsible for billions

of dollars worth of damage. The worm was nothing special, but it was sufficiently

different to the last e-plague, Melissa, that it sailed past virus

scanners and into Windows' e-mail programs everywhere.

With far more to protect than the average computer user, Sandia National Laboratories are busy training an agent to recognise and kill viruses, worms and other invaders before they do damage. Steve Goldsmith is lead scientist on the project. His assessment of his agent's abilities is blunt: "If every node on

the Internet was run by one of these agents, the I-Love-You virus would

not have got beyond the first machine."

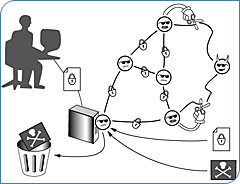

The agent isn't a Bond or an Ethan Hunt or even an Übergeek like one of the X-Files' Lone Gunmen. He's... well more like the browser you're using to view this site. The agent is software. You may know these agents as "bots" and if you've spent anytime on the Internet, you've probably already benefited from their actions. The most common bots are the spiders or crawlers, that access Web sites and gather their content for search engine indexes. Bots and software agents differ from conventional software in that they are semi-autonomous. Once given goals, agents can act, react and adapt without supervision. The hope is that adaptive agents will combat the biggest problem with current computer security: inflexibility. Ray Parks is leader of Sandia's government and corporate computer defence testing group, government paid hackers known as the Red Team. He puts the problem like this: "New stuff is coming along that you don't even know exists. Your software doesn't recognise it. Current defenses work as virus checkers; they recognise only specific virus patterns." In March 2000, Parks and his Red Team attacked a five computer network at Sandia protected by recently developed security bots known as cyberagents. The attack failed. The cyberagents, without outside assistance, held off four, experienced, human hackers for 16 hours. After the unsuccessful attack, Parks considers the cyberagent a worthy

opponent. "It will recognise odd attacks. It will turn off services, close

ports, go to alternate means of communication, and tighten firewalls,"

he explained.

What sets the Sandia cyberagent apart is that, unlike other bots, it is both an individual and a collective. The agent runs on multiple computers in a network and depending on circumstances the separate copies of the agent can act alone or together as a single, distributed program. The agents across the network constantly compare notes to determine if any unusual requests or commands have been received from external or internal sources. Their continuous vigilance means the system can recognise a threat by itself rather than waiting for software writer to identify a problem, figure out a defence and put it into a virus checker. The agents detect and deal with even the subtlest attacks or information gathering:

No central authority operates the agent. Instead, decentralised control makes each agent autonomous yet cooperative. So, no single point of attack can bring down the collective. The multi-agent program can also send out probes to locate and assess its attacker. "It's a sophisticated program," says Goldsmith. "For example, it replaces old agents by fresh agents periodically. This ensures that hacked systems are flushed eventually and must be re-hacked to be compromised." In fact it's so sophisticated it's almost life-like. An agent's entire structure is described by a program 'genome.' Download a genome and it grows a new agent from scratch. Once it's born, it connects immediately to other agents and becomes a member of the security community. This virus-like replication makes the agent easy to deploy in large numbers on the Internet... Resistance certainly appears to be futile. The cyberagents' ability to respond quickly when faced with a vast number of attacks and to colonise new territory even more quickly means it's not only an improvement on old virus scanners, in a purely computer security sense, it's an improvement on people. "Never send a human to do a machine's job" says Sandia researcher Laurence Phillips. "The cyberagent is a program acting under its own recognisance, and not under the direct control of an operator...Humans aren't fast enough. A person sitting at a terminal cannot protect you from Internet attack that is coming from everywhere in large masses of data." Cyberagents need to be faster than human beings because they are designed

to go up against far bigger guns than Melissa or I-Love-You.

"We're less concerned with the teen-aged kid and more with the serious

agents from foreign governments or foreign corporations who may take a

long time, very gently probing to understand where computers are that they

can take over or compromise," says Goldsmith. "On command, they can be

made to act as a supercomputer to attack a target, as happened recently,

or crack a privacy code intended to protect financial, medical, or other

critical data."

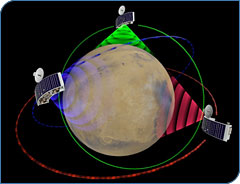

In time the agents may graduate from patrol to control. Intelligent agents would be ideal for the control of interplanetary robot swarm missions while at the same time protecting them from long distance hackers or practical jokers. Closer to home micro-satellite swarms or perhaps even remote-controlled jet fighters could be computer-coordinated with agent assistance. For now the plan is to ready the basic agent for specific applications in business and government by next year. A consumer release is at least three years away as Sandia says the agent must be "trained to protect a wider variety of services" before it can be of much use to the average household. One suspects it also needs to be dumbed down slightly so that it is not quite as clever as the military-grade version. Agents in the form of bots are already out there helping consumer get the best prices for on-line goods or collecting sites for search engines, but the speed, stability, and adaptability of these new multi-agents may mean they'll end up replacing these and other programs. Goldsmith believes that, "Interested consumers or businesses could form secure coalitions against hackers, and they will need to. The home computer is going to be connected to the Internet 24 hours a day, seven days a week with high-speed systems like DSL or cable modem. People will become the target of attacks." What kind of attacks with these be? Well if these agents are as good as Sandia says you can bet it won't be long be before the bad guys get some bots of their own and start using them against governments, corporations and the general public. Only time will tell if the development of Sandia's cyberagents just made Cyberspace safer or more dangerous. |

|

|

|

||

I

AM LEGION

I

AM LEGION Cyber

Agents

Cyber

Agents

Licensed

To Shut Down

Licensed

To Shut Down

Never

Send A Human To Do A Machine's Job

Never

Send A Human To Do A Machine's Job

Talk

to My Agent

Talk

to My Agent