![[E-mail this story]](emailthisstory.gif)

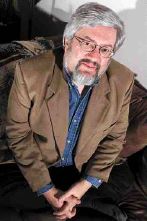

Peter Redman, National Post

HERO OR HOAX?: Peter de Jager wrote Doomsday

2000, leading to a globe-trotting schedule and $12,500 speaking fees.

|

Peter Redman, National Post

Devasted by the reaction.

|

Peter de Jager, the Brampton, Ont., man who dedicated a decade of his life to fighting the Y2K computer problem, sits slumped on the leather sectional sofa in his family room with a copy of an e-mail in his hand.

It is an excerpt from an article that ran in London's The Times earlier this month. The important excerpt is a few phrases long. "... the world had been suckered ... into wasting hundreds of billions of dollars on the most expensive confidence trick in history, the millennium bug."

A year ago, Mr. de Jager was the world's foremost expert on the Y2K computer problem that many believed would cause computer systems to collapse because their software mistook the double zeroes of 2000 to mean 1900. He wrote the seminal Doomsday 2000 article that did the most to initially publicize the problem, then spent the 1990s flying across the world, helping companies fix their computers. His Web site, year2000.com, was the world's clearing house for bug-related information.

Today, our Y2K worries seem an inexplicable and faintly embarrassing episode of history, similar to the "Who shot J.R.?" craze or the popularity of Duran Duran. The public myth has Mr. de Jager fleecing the world of the estimated $300-billion that was spent investigating and fixing the Y2K bug. When the problems failed to materialize, according to the myth, Mr. de Jager ducked out of public view, giggling softly at his seven-figure bank account balance.

The reality is something altogether different. A year after the most popular topic at the office photocopier was whether to fill your bathtub with water come New Year's Eve, I drove out to Brampton to spend the morning at the de Jager home.

At 45, Peter de Jager looks to be made from the same mould as Dom DeLuise and Paul Prudhomme. He has silver hair flecked with black, and wears a denim shirt and black slacks. When he moves, he makes that sound of audible nostril-breathing that only big people make.

Mr. de Jager was a semi-successful computer consultant when he first heard of the Y2K problem in 1991.

Two years later he wrote an article for Computerworld magazine that did more to publicize the problem than anything before. (The article was not the first public airing of the bug; Mr. de Jager has a photocopy of a 1986 advertisement mentioning the problem).

Mr. de Jager's first article says, basically, that if programmers don't take care of the problem, some computers will break down on New Year's Eve 2000.

It is a straightforward recitation of the problem and the consequences of not fixing it. The most apocalyptic thing about the article is the title: Mr. de Jager says he did not pick it.

Two years later, Mr. de Jager found himself skipping across the globe. The Doomsday 2000 article had pushed him to the centre of the effort to fix the bug, and he became a highly paid consultant to the many organizations looking for guidance about the problem. There were stretches of six weeks at a time when he was in a different city every day. He spoke before the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland. An article he wrote appeared in the widely respected magazine, Scientific American.

To understand the way Peter de Jager feels today, it is necessary to realize that he felt his Y2K work was doing the world a service. He stops short of saying he was working to save the world, but it is clear there were times when that is what he believed. In the years leading up to Y2K, Mr. de Jager's father and brother both died from cancer (at separate instances). He was not present at either of their deaths because he was off talking about Y2K. "This was important work," he says.

Sure, he may have liked the attention we gave him. For a semi-successful management consultant from Brampton, Ont., it must have been intoxicating to find yourself the world's Y2K guru. He was interviewed by the world's biggest news shows. Limousines picked him up at airports. But he also was so devoted to saving the world from Y2K that he turned down several business opportunities that would have made him rich. With years to go before Y2K, one company offered him $3-million for his site, year2000.com. Why didn't he accept the offers? "Because that wasn't the objective," Mr. de Jager says.

What was the objective?

"To fix the problem!"

Finally, during 1998, Mr. de Jager's work began to pay off. The financial sector was solving the problem, as were telecommunications companies, and the power companies finally were beginning to move. A few months later Mr. de Jager posted an article called Doomsday Avoided on his Web site. "We've finally broken the back of the Y2K problem," he proclaimed. "The Y2K problem was never the actual act of fixing the code ... it was the inaction and denial ... Have we solved Y2K? No, not entirely. But we have avoided the doomsday scenarios."

Writing Doomsday Avoided should have been Peter de Jager's moment of vindication. For years no one listened to him. People called him insane when he told them about the Y2K bug. Now, not only were people listening to him, they were doing something about it. His life's crusade was fulfilled.

But vindication soon gave way to frustration. Mr. de Jager could not stop the ball he had started to roll. Y2K anxiety continued to grow because the computer bug satisfied a deep-rooted social need. It was an excuse for two mass anxieties. The technophobes were uncomfortable with society's reliance on computers. Y2K gave the technophobes a reason for their discomfort. And all of the twaddle about Revelations and Nostradamus, and Armageddon and the Apocalypse fomented considerable religious anxiety. With or without the Y2K bug, those fast-approaching triple zeroes would have made some people nervous. Y2K was a less silly explanation for their anxiety.

Looking back, it all seems so silly. Hollywood killed a Chris O'Donnell movie about an apocalyptic Y2K, and the media speculated the U.S. government was worried about blockbusters triggering public hysteria. A book telling the story of a Y2K-caused economic collapse sold more than 200,000 copies. Home Depot sold out of electrical generators. IBM's in-house magazine advised workers to stock up on non-perishable goods and keep some extra cash on hand along with a supply of blankets and flashlights in case of power failures. Around the same time, the U.S. Federal Reserve released $200-billion to defend the banks from a mass cash withdrawal spurred by apocalyptic panic.

Mr. de Jager, meanwhile, was convinced Y2K would pass uneventfully. Still, the reporters called him. "Aren't you a little nervous?" "No," Mr. de Jager replied. "Not even a little?" It frustrated Mr. de Jager. He would show those pesky reporters -- he'd spend New Year's on a plane!

On the evening of New Year's Eve, Mr. de Jager kissed his wife and boarded the transatlantic flight. At 10 seconds to midnight the pilot began his countdown. "Understand, I was living and breathing Y2K," he says. "I had absolutely no concern." The New Year hit, the plane stayed aloft. "I'm officially unemployed," Mr. de Jager proclaimed to a reporter who was on the flight with him.

Early on New Year's morning, Mr. de Jager awoke in a London hotel room to the ringing of a telephone. Another reporter. "So it was all a hoax!" the reporter said. Later, interviewers alleged he was a shyster. He spoke to dozens of reporters that week and each time the spiel was the same. He was a confidence man. The whole thing was a sham -- right? "No!" Mr. de Jager said, frustrated.

Mr. de Jager did not have a good January. He was devastated by the world's reaction. He put his Web site up for sale on Internet auction site eBay and watched as the bids increased to the millions. They turned out to be hoaxes. Nasty letters poured into his e-mail inbox. Someone left a death threat on his answering machine. Mr. de Jager sank into a deep depression.

He still has not fully recovered. Perhaps he would feel better if he had made a fortune from the Y2K thing, but his stint as guru to the world did not leave him a rich man. Sure, he charged $12,500 per speech, but he also had a staff of eight working beneath him. He says he netted about $100,000 a year during the late 1990s. The de Jager house is the home of a lower-middle class family.

It is a three-bedroom, semi-detached unit in a suburb that is dense with similar homes. He has a one-car garage. His walls are decorated with tired-looking macramé. His Christmas tree is synthetic.

"I never got into this thing to be thanked ... but to be vilified for achieving it -- that's a cheat. That's where I felt cheated. Ignore me or forget me, but to suggest the work was pointless ..."

That a few random people remain unconvinced that the Y2K bug was a threat to many computer systems bothers Mr. de Jager.

His cellar is filled with sturdy cardboard boxes that store an archive of press clippings about the Y2K bug. It is easy to imagine him spending hours riffling through these boxes, the way a former star athlete might wear his sports jersey, or a child star watches tapes of his television shows. On his leather couch, Mr. de Jager shows me an article to prove how he has been mistreated. The first few paragraphs refer to the Y2K problem as a hoax.

"That's a blatant lie!" Mr. de Jager says, his voice breaking.

Sometimes when Mr. de Jager gets upset he speaks about himself in the third person. He begins to talk about many people's belief that his prime motivation for working on the Y2K bug was financial gain. "He didn't own any Y2K stock," Mr. de Jager says, referring to himself. "He turned down two huge endorsements, he didn't sell the Web site ... so if he was after the money, then he was an idiot." He leans forward so that his considerable gut rolls over his belt. "Because he could have made a pile of money." His voice sinks to a whisper, and he says, "He could have made a pile of money."