Security vs. Rebuilding: Kurdish Town Loses Out

Posted by archive

Security vs. Rebuilding: Kurdish Town Loses Out

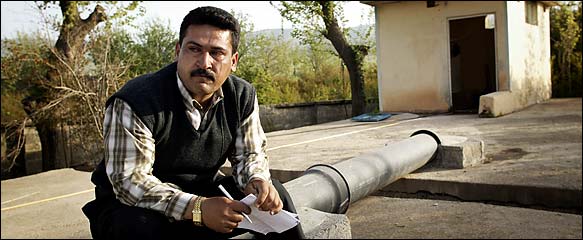

Christoph Bangert/Polaris, for The New York Times Nuradeen Ghreeb, a civil engineer, dreamed of bringing clean drinking water to his hometown, Halabja, but the United States canceled its planned water project there this week.

By JAMES GLANZ

Published: April 16, 2005

Source

HALABJA, Iraq, April 11 - For years Nuradeen Ghreeb has dreamed of bringing clean drinking water to his hometown. That town happens to be Halabja, where 17 years ago he and his parents cowered in a basement as Saddam Hussein's airplanes attacked with chemical weapons, killing at least 5,000 people.

But on Sunday, Mr. Nuradeen learned that his dream was over, because the United States had canceled the water project it had planned here as part of a vast effort to rebuild Iraq after the 2003 invasion. Ordinarily a quiet and reserved civil engineer, he sat on one of his beloved water pipes on hearing the news and wept, his tears glistening in the afternoon sun.

"If the Americans think that training the Iraqi Army comes before clean drinking water for the people of Halabja," he said quietly, "then we can't expect anything from them."

The Halabja project, worth around $10 million, accounted for a small fraction of the $18.4 billion that Congress approved in 2003 for the reconstruction of Iraq, including $4 billion for water and sewage projects. But with the outbreak of insurgency in central and southern Iraq last year, the United States shifted $3.4 billion from water, electricity and oil projects to pay for training and equipping the Iraqi Army and police forces.

The implications of that shift are only now becoming clear as individual projects are canceled in scores of communities across the country. Some of the largest cuts have come in waterworks: of 81 water projects that were to be financed through the Public Works Ministry, all but 13 have been canceled, with many of the rest reduced in scale, ministry officials say.

The project in this northern Kurdish town, where Mr. Nuradeen has been head of water and sewage projects since 2001, was one of those to lose out.

"They cut Halabja, of all places," said Nesreen M. Siddeek Berwari, the national public works minister, who happens to be Kurdish. "I'm outraged and amazed. Where else is it more important to do a water project?"

No more than 50 percent of Halabja's population has regular running water, and even that may be contaminated by bat feces from the mountain cave where much of the water originates.

In November a delegation from the Environment Ministry visited the town and found that contamination of its water supply could be connected with abnormalities found in residents' white and red blood cell counts and the relatively high levels of kidney disease, miscarriages and other maladies that have been reported here.

Mr. Nuradeen became anxious about the project a few weeks ago when he heard rumors from relief organizations that it might have been cut. But none of the officials and contractors who had promised the project bothered to inform him of the cancellation, and he learned the full facts only on Sunday, when a reporter relayed information collected in Baghdad at the Public Works Ministry and the American Embassy.

Mr. Nuradeen, a chunky man with a broad face, looking very much the staid engineer in his sleeveless gray sweater and checked shirt, struggled to maintain his composure as he heard the news, seated on the water pipe, assiduously taking notes. Then he began sobbing.

"Everybody uses Halabja like a card," he said finally. "But when it comes to working in Halabja, nobody does it."

Along with most of the people in Halabja and its surrounding villages, about 100,000 in all, Mr. Nuradeen is very aware of the symbolic role their town has had in helping to justify the invasion of Iraq. Local residents also understand the central importance that the mass graves in the local cemetery will have in the impending war crimes trials of Mr. Hussein and Ali Hassan al-Majid, known as Chemical Ali.

While American officials hold that the shift of billions of dollars from reconstruction to security was essential for maintaining stability in Iraq, the tradeoff carries a special resonance in Iraqi Kurdistan, where pesh merga fighters resisted Mr. Hussein's army for decades and have handily kept the peace since 2003.