'..inflation and unemployment .. that are the targets of central bank policy.'

Posted by archive

<i>'It’s endlessly fascinating to hear central bankers talk about the effect of monetary policy on inflation and the economy, because they confidently speak as if the models in their heads are true - even reliable. Yet virtually nothing they say can actually be </i>demonstrated<i> in historical data, and the estimated effects often go entirely in the opposite direction. This is particularly true when it comes to inflation and unemployment - precisely the variables that are the targets of central bank policy.

..

The long-term value of paper money relies on the confidence that someone else in the future will accept it in exchange for value, and ultimately, that’s a matter of varying confidence in the ability of the government to meet its long-term obligations. Early U.S. money such as confederate currency went to zero because that confidence was absent. Greenbacks held their value because of the expectation (validated in 1879) that convertibility with gold would ultimately be honored. Gold convertibility isn’t necessary, nor are balanced budgets required in the short-run, but confidence in long-run fiscal discipline is essential. If that confidence weakens - which may occur later in this decade, after the next recession - rapid inflation may emerge out of nowhere, and nobody will celebrate it.

..

Ultimately, QE may finally create inflation by provoking a loss of </i>fiscal<i> control..'</i>

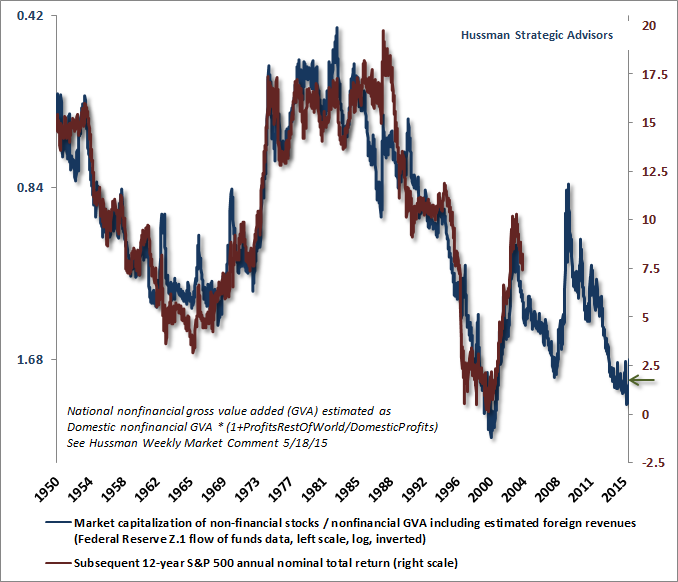

<blockquote>'The chart below shows the ratio of market capitalization to corporate gross value added on an inverted log scale (blue line, left scale), and the actual S&P 500 nominal annual total return over the following 12-year period (red line, right scale). For a mathematical decomposition, see Rarefied Air: Valuations and Subsequent Market Returns, which details why subsequent total returns are so strongly correlated with the log valuation ratio, and why the effects of changing interest rates and fundamental growth systematically offset each other over a 10-12 year holding period.

<center> </center>

</center>

Value investor Seth Klarman once wrote that “value investing is at its core the marriage between a contrarian streak and a calculator.” Benjamin Graham wrote "Buy not on optimism, but on arithmetic." Unfortunately, at every speculative peak, a different message emerges, suggesting that the calculator is broken, that “this time is different,” and that “the old valuation measures no longer apply.”

As John Kenneth Galbraith wrote decades ago about the advance to the 1929 peak, “as in all periods of speculation, men sought not to be persuaded by the reality of things but to find excuses for escaping into the new world of fantasy." Be skeptical of measures that show stocks reasonably valued today, but that are not strongly correlated with actual subsequent market returns in prior cycles across history. Be even more skeptical when most of the data is drawn from the past 16 years, because as noted above, the nominal total return of the S&P 500 over the past 16 years has been just 3.6% annually. Be particularly wary of arguments that propose that valuation doesn’t matter at all.

..

Global central bankers are locked in a contest to find out who can create the most psychotic variant of quantitative easing, Ben Bernanke’s grotesque brainchild, before irretrievably destabilizing the global financial system once again. Attached to an incorrect understanding of the Phillips Curve (which is actually a relationship between unemployment and wage inflation, and real wage inflation at that), central bankers seem to overlook that quantitative easing provokes neither inflation, nor employment, nor industrial production, nor real investment, nor consumption. The entire operation involves buying up income-producing bonds and replacing them with zero-interest money. Since every dollar of monetary base has to be held by someone until it is retired, the goal of QE is to provoke discomfort with the form in which investors are forced to hold their savings. That doesn’t encourage people to save less. They just look for alternative forms of saving.

..

As for the effect of QE on the real economy, economists have known since the 1950’s that people base their consumption on what they view as their “permanent” income, not on the fluctuating value of volatile assets. Indeed, Bernanke himself wrote an empirical paper on the subject in 1981, and concluded “The response of expenditure to transitory income changes is as predicted by the permanent income model.” Put simply, there’s no theoretical or factual basis to expect a “wealth effect” to benefit economic activity as a result of Fed bubble-blowing in the financial markets.

The “counterfactual” of how the economy would have done without this intervention is readily available. Good macroeconomists know that this involves comparing the projections from a constrained and unconstrained vector autoregression (VAR). Regardless of whether one uses observable or “shadow” monetary measures (as Wu-Xia do), the result is the same: all of this reckless intervention has hardly moved the level of employment, industrial production, or real GDP even 1% from what one would have predicted based on the values of purely non-monetary variables alone.

It’s endlessly fascinating to hear central bankers talk about the effect of monetary policy on inflation and the economy, because they confidently speak as if the models in their heads are true - even reliable. Yet virtually nothing they say can actually be demonstrated in historical data, and the estimated effects often go entirely in the opposite direction. This is particularly true when it comes to inflation and unemployment - precisely the variables that are the targets of central bank policy.

For example, study a century of data and you’ll discover that few economic series, not changes in money growth, not even unemployment, are strongly correlated with inflation - with the exception of prior inflation itself, and only by extension, the level of interest rates. The GDP output gap can also be useful, but the relationship with inflation isn’t quite linear - the main value is to discriminate between “tight capacity getting tighter” and “slack capacity getting slacker.”

Since inflation is correlated from year-to-year, an above-average level of inflation in one period is typically followed by an above-average level of inflation the next. But inflation also tends to mean revert, so a high level of inflation in one period is typically followed by a slower rate of inflation the next period.

As for cyclical behavior, the strongest plunges in the rate of inflation follow points where a) real GDP is below estimated potential GDP and b) that output gap has worsened in the past year. The retreat in inflation tends to be particularly large if the rate of inflation has increased over the prior year despite those conditions. Conversely, inflation accelerates most reliably when a) real GDP is above estimated potential GDP and b) that output gap has improved in the past year, regardless of the level of unemployment. Notably, once information on the output gap and inflation itself is included, additional information about monetary policy doesn’t materially improve projections of inflation. That’s another way of saying that only the systematic component of monetary policy (e.g. what could be captured by a simple Taylor Rule) is relevant to the economy. Activist deviations from systematic policy don’t do anything but distort financial markets.

Beyond those general rules of thumb, what drives inflation? While many economists seem satisfied with having memorized a line from Milton Friedman about inflation being “always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon,” economic models of inflation turn out to be nearly useless for any practical purpose. It’s not difficult to explain inflation, using inflation itself as the main explanatory variable, and information on the output gap is also useful even if unemployment is not. But it’s very difficult to explain most episodes of inflation using monetary variables.

Yes, hyperinflation is always associated with monetary expansion, but monetary expansion isn’t actually enough. Examine major hyperinflations, and you’ll always find a government that has racked up huge external obligations to other countries, and has lost fiscal control by running massive deficits - effectively printing money to fund them. Hyperinflation involves a loss of both fiscal and monetary control, often coupled with a supply shock of some sort, and revulsion toward holding money itself because the willingness of the next person to accept it comes into question.

The long-term value of paper money relies on the confidence that someone else in the future will accept it in exchange for value, and ultimately, that’s a matter of varying confidence in the ability of the government to meet its long-term obligations. Early U.S. money such as confederate currency went to zero because that confidence was absent. Greenbacks held their value because of the expectation (validated in 1879) that convertibility with gold would ultimately be honored. Gold convertibility isn’t necessary, nor are balanced budgets required in the short-run, but confidence in long-run fiscal discipline is essential. If that confidence weakens - which may occur later in this decade, after the next recession - rapid inflation may emerge out of nowhere, and nobody will celebrate it.

Now, expansionary fiscal policies are fine when they result in the accumulation of productive capital by society (which can include infrastructure, workforce training, and even support for productive investment by fiscal means such as tax credits). Put simply, productive investment is the best avenue to expand potential GDP, increase employment, and reduce the likelihood of inflation. But when the primary use of fiscal policy is to wipe up the catastrophe of weak productivity, lost income, unemployment, and malinvestment created in the repeated aftermath of collapsed financial bubbles, the endgame is going to be stagnant living standards and a debased currency.

Ultimately, QE may finally create inflation by provoking a loss of fiscal control. My concern is that central banks have risked just that by encouraging yet another speculative bubble, heavy issuance of low-grade debt, and the diversion of savings toward unproductive investment. The inevitable fiscal consequences are likely to include bailouts, as well as urgency to expand income-replacement and transfer payment programs as the third bubble since 2000 collapses (which QE will helpless to prevent so long as investors remain risk-averse). Europe is approaching that endgame, and last week’s action by the ECB is evidence of increasing panic. Other economies are not far behind. The greatest risk is that Mario Draghi and other central bankers may ultimately get their wish for higher inflation, but not at all as they intend.'

- John P. Hussman, Ph.D., Bearishness Is Strictly For Informed Optimists, March 14, 2015</blockquote>

Context

<blockquote>'..epic financial and economic impairment..'

Deflation Defeats Impotent Central Banks, March 1, 2016

'..without taking any care to reduce the size of its balance sheet, the Federal Reserve instantly changed the monetary environment..'

'..recessions are not primarily driven by weakness in consumer spending..'

'..Credit, inflationism and resulting central bank-induced monetary disorder.'

'..the Federal Reserve’s deranged program of quantitative easing..'</blockquote>

..

The long-term value of paper money relies on the confidence that someone else in the future will accept it in exchange for value, and ultimately, that’s a matter of varying confidence in the ability of the government to meet its long-term obligations. Early U.S. money such as confederate currency went to zero because that confidence was absent. Greenbacks held their value because of the expectation (validated in 1879) that convertibility with gold would ultimately be honored. Gold convertibility isn’t necessary, nor are balanced budgets required in the short-run, but confidence in long-run fiscal discipline is essential. If that confidence weakens - which may occur later in this decade, after the next recession - rapid inflation may emerge out of nowhere, and nobody will celebrate it.

..

Ultimately, QE may finally create inflation by provoking a loss of </i>fiscal<i> control..'</i>

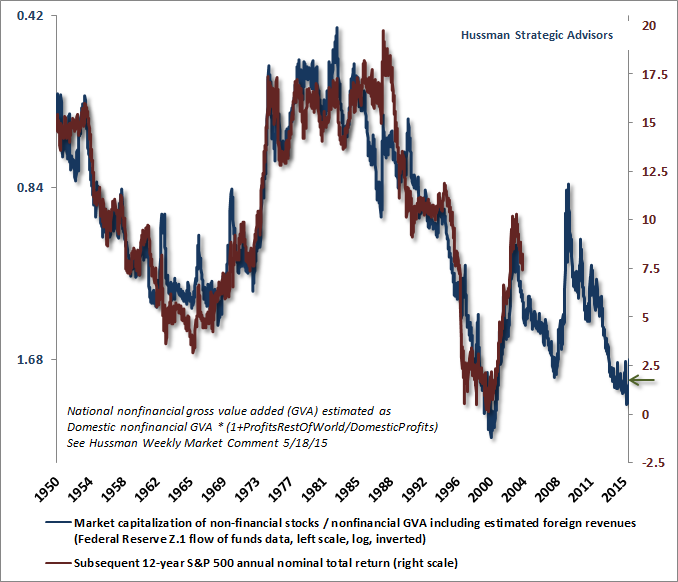

<blockquote>'The chart below shows the ratio of market capitalization to corporate gross value added on an inverted log scale (blue line, left scale), and the actual S&P 500 nominal annual total return over the following 12-year period (red line, right scale). For a mathematical decomposition, see Rarefied Air: Valuations and Subsequent Market Returns, which details why subsequent total returns are so strongly correlated with the log valuation ratio, and why the effects of changing interest rates and fundamental growth systematically offset each other over a 10-12 year holding period.

<center>

</center>

</center>Value investor Seth Klarman once wrote that “value investing is at its core the marriage between a contrarian streak and a calculator.” Benjamin Graham wrote "Buy not on optimism, but on arithmetic." Unfortunately, at every speculative peak, a different message emerges, suggesting that the calculator is broken, that “this time is different,” and that “the old valuation measures no longer apply.”

As John Kenneth Galbraith wrote decades ago about the advance to the 1929 peak, “as in all periods of speculation, men sought not to be persuaded by the reality of things but to find excuses for escaping into the new world of fantasy." Be skeptical of measures that show stocks reasonably valued today, but that are not strongly correlated with actual subsequent market returns in prior cycles across history. Be even more skeptical when most of the data is drawn from the past 16 years, because as noted above, the nominal total return of the S&P 500 over the past 16 years has been just 3.6% annually. Be particularly wary of arguments that propose that valuation doesn’t matter at all.

..

Global central bankers are locked in a contest to find out who can create the most psychotic variant of quantitative easing, Ben Bernanke’s grotesque brainchild, before irretrievably destabilizing the global financial system once again. Attached to an incorrect understanding of the Phillips Curve (which is actually a relationship between unemployment and wage inflation, and real wage inflation at that), central bankers seem to overlook that quantitative easing provokes neither inflation, nor employment, nor industrial production, nor real investment, nor consumption. The entire operation involves buying up income-producing bonds and replacing them with zero-interest money. Since every dollar of monetary base has to be held by someone until it is retired, the goal of QE is to provoke discomfort with the form in which investors are forced to hold their savings. That doesn’t encourage people to save less. They just look for alternative forms of saving.

..

As for the effect of QE on the real economy, economists have known since the 1950’s that people base their consumption on what they view as their “permanent” income, not on the fluctuating value of volatile assets. Indeed, Bernanke himself wrote an empirical paper on the subject in 1981, and concluded “The response of expenditure to transitory income changes is as predicted by the permanent income model.” Put simply, there’s no theoretical or factual basis to expect a “wealth effect” to benefit economic activity as a result of Fed bubble-blowing in the financial markets.

The “counterfactual” of how the economy would have done without this intervention is readily available. Good macroeconomists know that this involves comparing the projections from a constrained and unconstrained vector autoregression (VAR). Regardless of whether one uses observable or “shadow” monetary measures (as Wu-Xia do), the result is the same: all of this reckless intervention has hardly moved the level of employment, industrial production, or real GDP even 1% from what one would have predicted based on the values of purely non-monetary variables alone.

It’s endlessly fascinating to hear central bankers talk about the effect of monetary policy on inflation and the economy, because they confidently speak as if the models in their heads are true - even reliable. Yet virtually nothing they say can actually be demonstrated in historical data, and the estimated effects often go entirely in the opposite direction. This is particularly true when it comes to inflation and unemployment - precisely the variables that are the targets of central bank policy.

For example, study a century of data and you’ll discover that few economic series, not changes in money growth, not even unemployment, are strongly correlated with inflation - with the exception of prior inflation itself, and only by extension, the level of interest rates. The GDP output gap can also be useful, but the relationship with inflation isn’t quite linear - the main value is to discriminate between “tight capacity getting tighter” and “slack capacity getting slacker.”

Since inflation is correlated from year-to-year, an above-average level of inflation in one period is typically followed by an above-average level of inflation the next. But inflation also tends to mean revert, so a high level of inflation in one period is typically followed by a slower rate of inflation the next period.

As for cyclical behavior, the strongest plunges in the rate of inflation follow points where a) real GDP is below estimated potential GDP and b) that output gap has worsened in the past year. The retreat in inflation tends to be particularly large if the rate of inflation has increased over the prior year despite those conditions. Conversely, inflation accelerates most reliably when a) real GDP is above estimated potential GDP and b) that output gap has improved in the past year, regardless of the level of unemployment. Notably, once information on the output gap and inflation itself is included, additional information about monetary policy doesn’t materially improve projections of inflation. That’s another way of saying that only the systematic component of monetary policy (e.g. what could be captured by a simple Taylor Rule) is relevant to the economy. Activist deviations from systematic policy don’t do anything but distort financial markets.

Beyond those general rules of thumb, what drives inflation? While many economists seem satisfied with having memorized a line from Milton Friedman about inflation being “always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon,” economic models of inflation turn out to be nearly useless for any practical purpose. It’s not difficult to explain inflation, using inflation itself as the main explanatory variable, and information on the output gap is also useful even if unemployment is not. But it’s very difficult to explain most episodes of inflation using monetary variables.

Yes, hyperinflation is always associated with monetary expansion, but monetary expansion isn’t actually enough. Examine major hyperinflations, and you’ll always find a government that has racked up huge external obligations to other countries, and has lost fiscal control by running massive deficits - effectively printing money to fund them. Hyperinflation involves a loss of both fiscal and monetary control, often coupled with a supply shock of some sort, and revulsion toward holding money itself because the willingness of the next person to accept it comes into question.

The long-term value of paper money relies on the confidence that someone else in the future will accept it in exchange for value, and ultimately, that’s a matter of varying confidence in the ability of the government to meet its long-term obligations. Early U.S. money such as confederate currency went to zero because that confidence was absent. Greenbacks held their value because of the expectation (validated in 1879) that convertibility with gold would ultimately be honored. Gold convertibility isn’t necessary, nor are balanced budgets required in the short-run, but confidence in long-run fiscal discipline is essential. If that confidence weakens - which may occur later in this decade, after the next recession - rapid inflation may emerge out of nowhere, and nobody will celebrate it.

Now, expansionary fiscal policies are fine when they result in the accumulation of productive capital by society (which can include infrastructure, workforce training, and even support for productive investment by fiscal means such as tax credits). Put simply, productive investment is the best avenue to expand potential GDP, increase employment, and reduce the likelihood of inflation. But when the primary use of fiscal policy is to wipe up the catastrophe of weak productivity, lost income, unemployment, and malinvestment created in the repeated aftermath of collapsed financial bubbles, the endgame is going to be stagnant living standards and a debased currency.

Ultimately, QE may finally create inflation by provoking a loss of fiscal control. My concern is that central banks have risked just that by encouraging yet another speculative bubble, heavy issuance of low-grade debt, and the diversion of savings toward unproductive investment. The inevitable fiscal consequences are likely to include bailouts, as well as urgency to expand income-replacement and transfer payment programs as the third bubble since 2000 collapses (which QE will helpless to prevent so long as investors remain risk-averse). Europe is approaching that endgame, and last week’s action by the ECB is evidence of increasing panic. Other economies are not far behind. The greatest risk is that Mario Draghi and other central bankers may ultimately get their wish for higher inflation, but not at all as they intend.'

- John P. Hussman, Ph.D., Bearishness Is Strictly For Informed Optimists, March 14, 2015</blockquote>

Context

<blockquote>'..epic financial and economic impairment..'

Deflation Defeats Impotent Central Banks, March 1, 2016

'..without taking any care to reduce the size of its balance sheet, the Federal Reserve instantly changed the monetary environment..'

'..recessions are not primarily driven by weakness in consumer spending..'

'..Credit, inflationism and resulting central bank-induced monetary disorder.'

'..the Federal Reserve’s deranged program of quantitative easing..'</blockquote>