'..I’ve lost all respect for monetary economists..'

Posted by ProjectC

‘All things are subject to the law of cause and effect. This great principle knows no exception.’

- Carl Menger, The Founder of the Austrian School (Context)

'Contrast that with the large and persistent activist deviations that Alan Greenspan, Ben Bernanke and Janet Yellen have pursued under their leadership at the Fed. In each case, we observe aggressive departures from the Fed Funds rate that one would have projected based on current and lagged data on output, employment, and inflation .. those three large deviations helped to produce a series of three speculative bubbles in the financial markets; the first that ended with the technology collapse, the second that ended with the global financial crisis, and the third that has now brought reliable measures of valuation to one of the most offensive extremes in U.S. history. The problem is that these speculative consequences only emerge over a period of years..'

'The dogmatic insistence on pursuing policies based on assumptions rather than economic evidence; the failure to invest in the careful analysis of cause-and-effect relationships before consuming in the form of activist policy, is where I’ve lost all respect for monetary economists. They’ve jumped straight to consumption - pursuing recklessly experimental policies, without first establishing evidence that their tools have a reliable correlation with actual subsequent economic outcomes.

..

Does this mean that monetary policy is completely useless in affecting subsequent economic outcomes? Not so fast. We have to make a distinction between the “systematic” component of monetary policy that’s correlated with non-monetary variables (output, employment, inflation), and the remaining “activist” component. See, it’s possible that the systematic or rules-based component of policy is actually useful and necessary in producing economic outcomes. Since that systematic component overlaps or “spans the same space” as the non-monetary variables, we can’t rule out the possibility that it has legitimate effects. All we can say with confidence is that the activist component isn’t doing much, except to produce speculative episodes that negatively impact the economy when they collapse. But those effects emerge over a much more extended horizon.

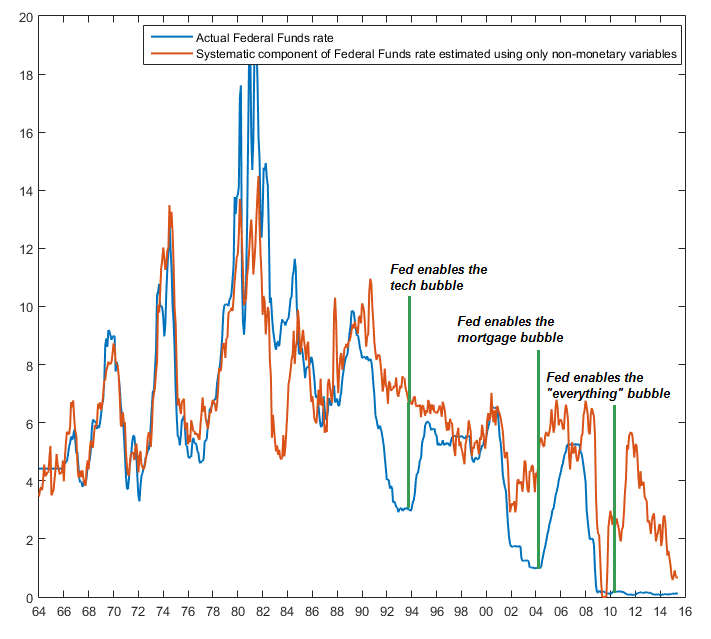

In the chart below, the blue line shows the actual Federal Funds rate over time, while the red line shows the systematic component. The difference between these two lines is what I’m calling the “activist” component of monetary policy.

You’ll notice a few things immediately. First, in the effort to break the back of inflation, Paul Volcker probably tightened monetary policy in 1981 a few percent beyond what might have been necessary, but it was also quite a brief deviation. Likewise, it’s possible that monetary policy could have been briefly loosened following the 1981-1982 recession somewhat more than it was in practice, but it’s clear that this was also a brief deviation. In the context of the disruptive inflation of the 1970’s, I have nothing but praise for the remarkable fidelity of monetary policy during Volcker’s tenure to a systematic and rules-based discipline. Since we observe nearly zero correlation between the “activist” component of monetary policy and subsequent economic outcomes, the most likely effect of Volcker’s additional tightness in 1982 was to help in driving the financial markets to their deepest level of undervaluation, and highest level of prospective future investment returns, in the post-war era.

Contrast that with the large and persistent activist deviations that Alan Greenspan, Ben Bernanke and Janet Yellen have pursued under their leadership at the Fed. In each case, we observe aggressive departures from the Fed Funds rate that one would have projected based on current and lagged data on output, employment, and inflation. In turn, those three large deviations helped to produce a series of three speculative bubbles in the financial markets; the first that ended with the technology collapse, the second that ended with the global financial crisis, and the third that has now brought reliable measures of valuation to one of the most offensive extremes in U.S. history. The problem is that these speculative consequences only emerge over a period of years. Indeed, the "activist" component of the Federal Funds rate has a correlation of -0.53 with the ratio of market capitalization/nominal GDP three years later. The two prior postwar valuation extremes in 2000 and 2007 were both followed by a loss of half the market value of the S&P 500 (with even deeper losses in technology and financial sectors, respectively). The disruptive consequences of this third episode are still ahead, and are now effectively baked-in-the-cake.

..

Think carefully about what the economists at Jackson Hole were really saying: “If you’ve worked hard, and saved, and want to provide for your future without joining in on the late-stage of a speculative bubble, then our job is to figure out how to punish you into abandoning those plans and consuming or speculating now. We’re really smart and well-intentioned people, and can’t imagine that repeated episodes of yield-seeking speculation and collapse could possibly be our doing, so the only solutions to be found must be those that expand the size, scope, and aggressiveness of our interventions. If zero interest rates aren’t enough, perhaps we can eliminate the lower bound entirely. If negative interest rates aren’t enough, then we need to wipe out your purchasing power by raising the inflation targets we already can’t hit. Sorry, it’s a trade-off. We can’t prove the benefits of that trade-off in actual data unless we’re super-careless about what we call evidence and only take credit for improvements, but let’s assume a tradeoff. QED.”

This delight in the technical details of pulling off something new, without evidence of human good, is how intelligent people lose their soul. It seems to me that monetary economists have fallen into that abyss. As the physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer wrote:

“When you see something that is technically sweet, you go ahead and do it and you argue about what to do about it only after you have had your technical success. That is the way it was with the atomic bomb.”

- John P. Hussman, Ph.D., Failed Transmission - Evidence on the Futility of Activist Fed Policy, September 5, 2016

Context (Banking Reform - English/Dutch) '..a truly stable financial and monetary system for the twenty-first century..'

'..saving, wise investment and production are what creates wealth, not spending and consumption..'

- Carl Menger, The Founder of the Austrian School (Context)

'Contrast that with the large and persistent activist deviations that Alan Greenspan, Ben Bernanke and Janet Yellen have pursued under their leadership at the Fed. In each case, we observe aggressive departures from the Fed Funds rate that one would have projected based on current and lagged data on output, employment, and inflation .. those three large deviations helped to produce a series of three speculative bubbles in the financial markets; the first that ended with the technology collapse, the second that ended with the global financial crisis, and the third that has now brought reliable measures of valuation to one of the most offensive extremes in U.S. history. The problem is that these speculative consequences only emerge over a period of years..'

'The dogmatic insistence on pursuing policies based on assumptions rather than economic evidence; the failure to invest in the careful analysis of cause-and-effect relationships before consuming in the form of activist policy, is where I’ve lost all respect for monetary economists. They’ve jumped straight to consumption - pursuing recklessly experimental policies, without first establishing evidence that their tools have a reliable correlation with actual subsequent economic outcomes.

..

Does this mean that monetary policy is completely useless in affecting subsequent economic outcomes? Not so fast. We have to make a distinction between the “systematic” component of monetary policy that’s correlated with non-monetary variables (output, employment, inflation), and the remaining “activist” component. See, it’s possible that the systematic or rules-based component of policy is actually useful and necessary in producing economic outcomes. Since that systematic component overlaps or “spans the same space” as the non-monetary variables, we can’t rule out the possibility that it has legitimate effects. All we can say with confidence is that the activist component isn’t doing much, except to produce speculative episodes that negatively impact the economy when they collapse. But those effects emerge over a much more extended horizon.

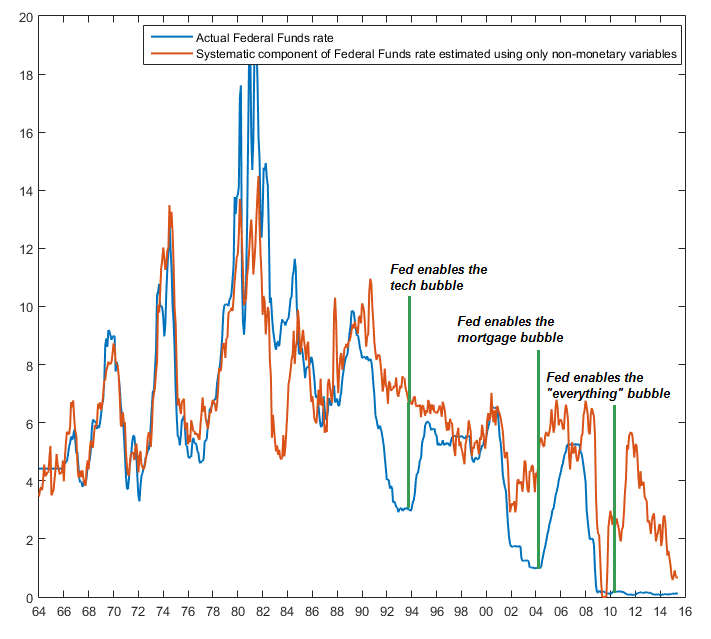

In the chart below, the blue line shows the actual Federal Funds rate over time, while the red line shows the systematic component. The difference between these two lines is what I’m calling the “activist” component of monetary policy.

You’ll notice a few things immediately. First, in the effort to break the back of inflation, Paul Volcker probably tightened monetary policy in 1981 a few percent beyond what might have been necessary, but it was also quite a brief deviation. Likewise, it’s possible that monetary policy could have been briefly loosened following the 1981-1982 recession somewhat more than it was in practice, but it’s clear that this was also a brief deviation. In the context of the disruptive inflation of the 1970’s, I have nothing but praise for the remarkable fidelity of monetary policy during Volcker’s tenure to a systematic and rules-based discipline. Since we observe nearly zero correlation between the “activist” component of monetary policy and subsequent economic outcomes, the most likely effect of Volcker’s additional tightness in 1982 was to help in driving the financial markets to their deepest level of undervaluation, and highest level of prospective future investment returns, in the post-war era.

Contrast that with the large and persistent activist deviations that Alan Greenspan, Ben Bernanke and Janet Yellen have pursued under their leadership at the Fed. In each case, we observe aggressive departures from the Fed Funds rate that one would have projected based on current and lagged data on output, employment, and inflation. In turn, those three large deviations helped to produce a series of three speculative bubbles in the financial markets; the first that ended with the technology collapse, the second that ended with the global financial crisis, and the third that has now brought reliable measures of valuation to one of the most offensive extremes in U.S. history. The problem is that these speculative consequences only emerge over a period of years. Indeed, the "activist" component of the Federal Funds rate has a correlation of -0.53 with the ratio of market capitalization/nominal GDP three years later. The two prior postwar valuation extremes in 2000 and 2007 were both followed by a loss of half the market value of the S&P 500 (with even deeper losses in technology and financial sectors, respectively). The disruptive consequences of this third episode are still ahead, and are now effectively baked-in-the-cake.

..

Think carefully about what the economists at Jackson Hole were really saying: “If you’ve worked hard, and saved, and want to provide for your future without joining in on the late-stage of a speculative bubble, then our job is to figure out how to punish you into abandoning those plans and consuming or speculating now. We’re really smart and well-intentioned people, and can’t imagine that repeated episodes of yield-seeking speculation and collapse could possibly be our doing, so the only solutions to be found must be those that expand the size, scope, and aggressiveness of our interventions. If zero interest rates aren’t enough, perhaps we can eliminate the lower bound entirely. If negative interest rates aren’t enough, then we need to wipe out your purchasing power by raising the inflation targets we already can’t hit. Sorry, it’s a trade-off. We can’t prove the benefits of that trade-off in actual data unless we’re super-careless about what we call evidence and only take credit for improvements, but let’s assume a tradeoff. QED.”

This delight in the technical details of pulling off something new, without evidence of human good, is how intelligent people lose their soul. It seems to me that monetary economists have fallen into that abyss. As the physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer wrote:

“When you see something that is technically sweet, you go ahead and do it and you argue about what to do about it only after you have had your technical success. That is the way it was with the atomic bomb.”

- John P. Hussman, Ph.D., Failed Transmission - Evidence on the Futility of Activist Fed Policy, September 5, 2016

Context (Banking Reform - English/Dutch) '..a truly stable financial and monetary system for the twenty-first century..'

'..saving, wise investment and production are what creates wealth, not spending and consumption..'